Zoinks!

Literary Madlibs

First, Some News

I’m grateful to have a new story in the fall issue of The Summerset Review called “Oversoul.” You can read it here. (Grab a beverage and a blanket. It’s long.) I had this idea for a character with perfect facial recognition way back when I was working in restaurants and kept seeing regulars all over the city. I’ve always been fascinated by limbo states, which, it seems to me, define much of our lives—deciding, mulling, wandering, afraid. Here’s my attempt at capturing that. Be sure to read the other stories in the issue, though, too. I really enjoyed Alice Kinerk’s “Homebodies.”

In case you missed it, I had a great time chatting with the fiction writer Justin Taylor a few weeks back. You writers out there might especially enjoy this. Justin had some great things to say about voice, research, and causality. Give it a go, and then be sure to read Reboot, one of my favorite novels last year.

It was fun to see László Krasznahorkai win the Nobel. He’s admittedly not for everyone, but if dark humor, bleakness, existential apocalypse, few paragraph breaks, and sentences that often stretch on for pages get you tittering, this might be your thing. I wrote about him a while back for VQR, which you can read if you have a subscription. You can find his work over at the formidable New Directions.

I’m off on a bike trip along the California coast later this morning, and after consulting some friends, I decided to pack Sigrid Nunez’s The Friend, which I’ve been avoiding for some reason, and Brad Watson’s Last Days of the Dog-Men, an old favorite. Our dog Fred passed away two weeks ago, and I’ve been missing him a lot, so I’ll likely be writing about fictional dogs in the next installment. Let me know if you have any favorites.

Okay, back to business.

+++

Zoinks!

Surprise, that is the quality I value above all else in fiction. I grew up around weirdos and strange happenings. People speaking in tongues and dads blowing gambling winnings on busted-out Camaros. Motivation felt more like impulse, addiction, and escape. Uncles made fun of aunts to their faces. Kids pulled other kids’ pants down in social studies. The assistant principal ogled the girls. And as I got older, friends backstabbed and lied, cheated and made fun of you.

We do whacked-out things every day—we tangle phrases, mix metaphors, greet each other with goofy gestures, say things we don’t mean, give backhanded compliments, justify our actions (to ourselves, to each other) with fuzzy logic, grapple toward challenge or toxicity with dubious motivations we have to parse out later and possibly atone for. We get bogged in guilt, excuses, foreign and domestic affairs, head-trips, day trips, DayQuil, night sweats. So, when I go to fiction the characters I spend time with need to be distinguished in some way—in speech, action, or thought.

Surprise is often, though not always, enacted on the level of the sentence. Sometimes you need some utilitarian sentences—cold shots of clarity to compass the way. But so many of these in a row can be a real bore. I don’t mean every sentence has to be an all-out stunner. Nobody wants to sit through an hour-long guitar solo at a rock show. But the licks, the triplets, the unexpected time-shifts: that’s where my attention is often earned and sustained. I know not everyone will take a liking to Gass, Lutz, and Schutt (Literary Litigators). Prose like theirs is akin to poetry, and some training or appreciation of poetics might be a prerequisite to their enjoyment, but even clear and precise writers like Claire Keegan know the art of surprise.

Plots, too. Surprise me. Tease me. Lead your lost character down an alleyway and push them into a butterfly house. Prince charming drops to his knee and cuts it on a broken Heineken bottle. Little bo peep lost her bleep and got her mouth washed out with soap. The plot twist, when done well, can bully you right out of the your seat and make you scream. Of course Abel Magwitch is Pip’s benefactor! Why hadn’t I thought of that?

This is not gospel, friends. Some of us like comfort food, indulgence, the safety of tropes, genre expectations, and predictability. No shade thrown. But as a teacher of literary fiction whose ambitions are literary, surprise, I would say, is a must.

I fear I’ll lose 59.3% of you if I start waxing poetic about the beauty of omitting conjunctions in list-style sentences, so let’s play a little game instead.

Try your darnedest to guess the answers to these literary Madlibs, which I’ll send out next week.

Literary Madlib #1

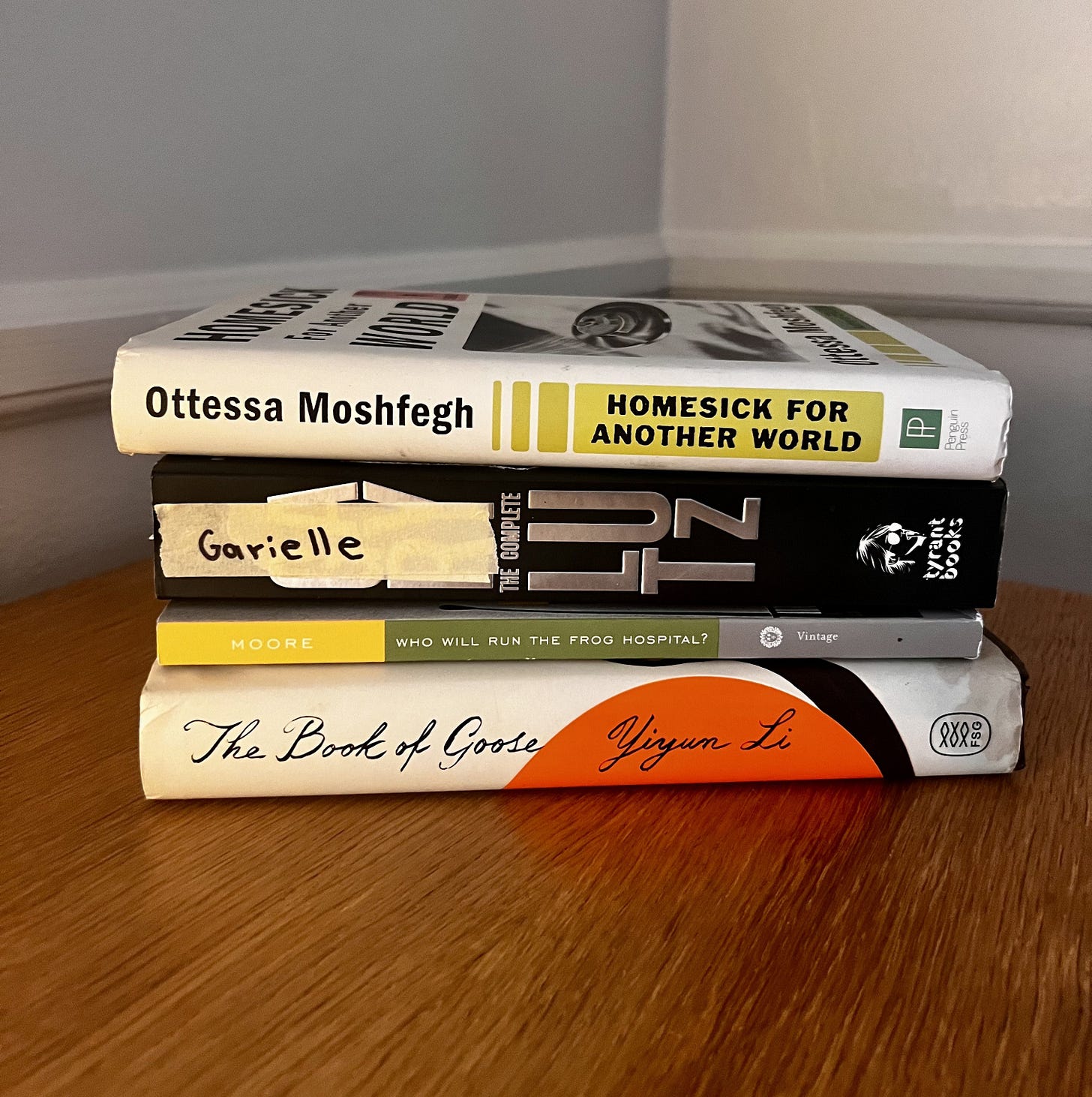

from Ottessa Moshfegh’s short story “The Weirdos”:

He told me I was the __(Noun, singular)__ he’d been waiting for and, like looking into a __ (Adj) __ __(noun, singular)__, he’d just read a private message from__( noun)__in the __(Adj) __(noun, singular)__of my left __(noun, singular)__.

Literary Madlib #2

Here’s an easier one, from Yiyun Li’s novel The Book of Goose:

Some people are born with a special kind of ___(Noun, singular)___instead of a heart. No, I am not talking about witchcraft, but it is a mystery that these people, who look no different than others, can sail through life without illness, injuries, or broken ___(noun, plural)___.

Literary Madlib #3

Here’s the opening of Lorrie Moore’s novel Who Will Run the Frog Hospital?:

In Paris we eat __(Noun, plural)__ every night. My husband likes the vaporous, __(Adj)__ mousse of them. They are a kind of seafood, he thinks, locked tightly in the __(noun)__, like shelled creatures in the dark caves of the ocean, sprung suddenly free and killed by light; they’ve grown __(Adj)__ with shelter, fortressed __noun__, dreamy nights. Me, I’m eating for a __(Noun)__.

Literary Madlib #4

And because no discussion about sentences can be made without mentioned Garielle Lutz, here’s a toughie, from “I Was in Kilter with Him, a Little.” (How about that title.)

I once had a husband, an __(Adj)__, __(Adj)__ man of forty, but I often felt carried away from the marriage. I was no __(Noun, singular)__, and he was largely a __(Noun, singular)__, minutely __(Adj)__ in his bearing.

I’ll admit this doesn’t work with all writers I like—picking a book from my shelf at random and plucking surprising sentences—but the element of surprise, in this age of unoriginal thought, algorithmic influence, and internet slobberboning is all the more pressing for artists.

(See. You thought I was going to say “slop” instead of “slobberboning.” It only takes a little more effort.)

Zoinks!