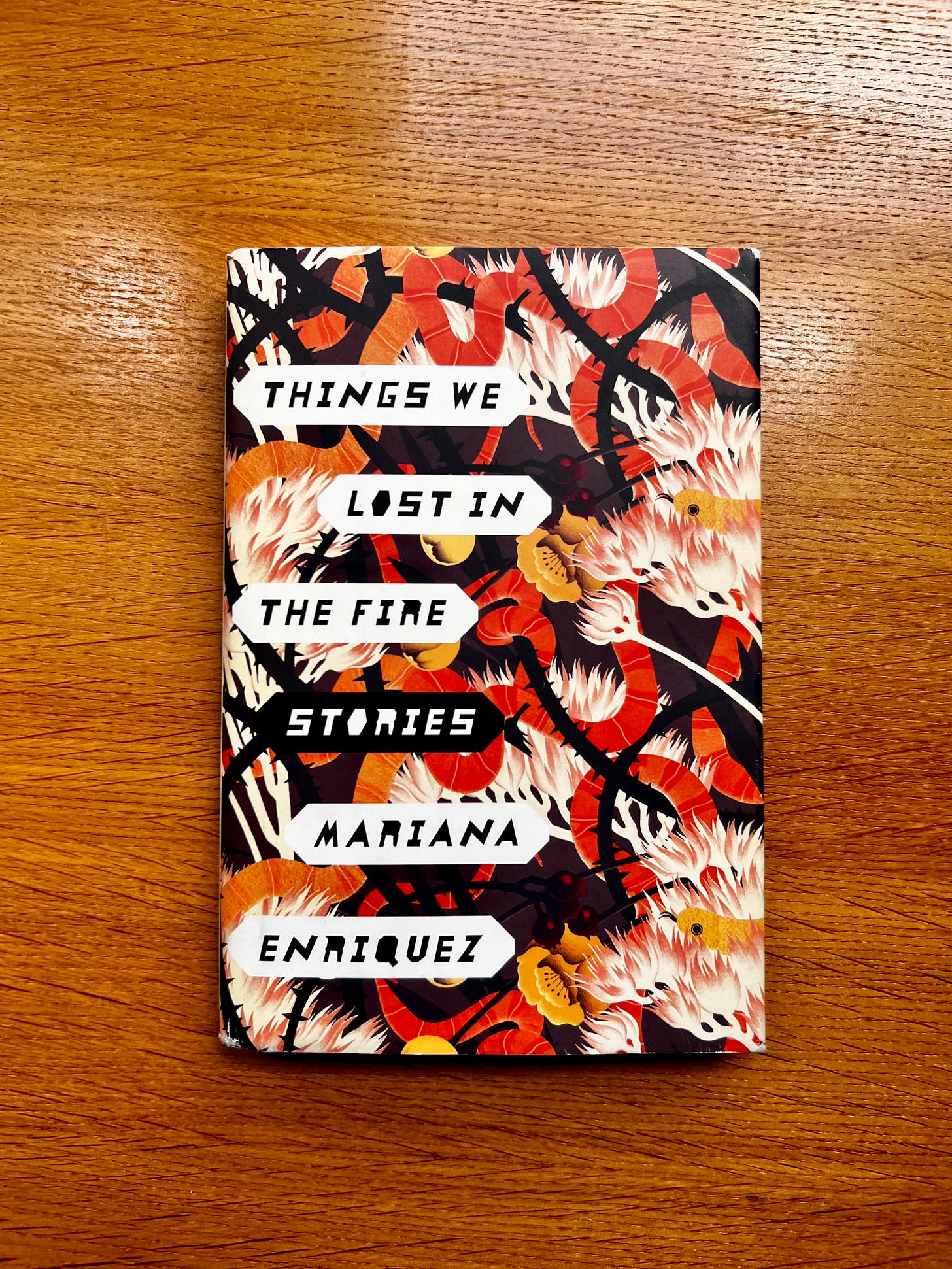

Things We Lost in the Fire

On Mariana Enríquez and the Importance of Getting Disturbed

First, Some News

I’m very happy to have a story in BULL literary magazine called “Lies I Tell My Daughter.” I would say the story is new, but it’s been living with me since 2016 when I was invited to participate in a short-lived but riotously fun reading series called 555. I had five minutes to read. Naturally, I wrote the beginning of a new story for that occasion but didn’t know how to develop it or end it, so it sat there on my desktop for three years until it finally clicked. And now, here we are—nine years, thirty-six rejections, and many revisions later. Thanks to Ben at BULL and to all my pals who’ve read and commented on this over the years.

Next, Catherine Lacey—whose newsletter and books are fantastic and you should absolutely consume—is hosting an irregular book club. The first pick was Sad Tiger by Neige Sinno, which I ordered but did not get in time to read. I’m sure I’ll be more prudent next time. Also, Garth Greenwell is also hosting a book club over on his Substack, To a Green Thought, and his first pick is Flesh by David Szalay, which has been on my list since it came out. I’m going to try to make it to the book club Zoom on August 24th. Join me? I’d love to see you in the great beyond.

While revising this newsletter, I got more good news about another story published. When the editor asked me to try a different ending, I sat in the backyard with my laptop, mulling it over and writing three different versions. After a while, my wife Rebekah came home and gave me the gift of an ending I hadn’t thought of. So, here’s to longterm love(s).

OK, back to business.

Things We Lost in the Fire: On Mariana Enríquez and the Importance of Getting Disturbed

Go outside and look. Just look. Look at the alliums, the coneflowers, and the milkweed. Look at the graffiti—the proclamations of love and the condemnations of institutions and systems, the monikers, “Ratboy” and “Slim69”—and see the sidewalk chalk and the tipped-over porta-potty. Look at the busted out lampposts all along the parkway, electrical panels pried open and stripped of copper wire. Look at the trees, the crowns, the burls, the oak leaves that look shellacked, the green acorns flung from trees by squirrels with no impulse control, the bees, the jays, the red-winged blackbirds. Look at the babies in the strollers and the chattering speedwalkers and see the reckless drivers blasting through the stop sign, the stumbling drunk people on the corner, the person sleeping on the bus bench. See the trash in the ravine, the needles in the wood chips at the playground, the great stack of cumulonimbus in the distance.

Everything has its own special path to catching our attention, as we are in and out of seasons and moods—solipsism and great, expansive empathy. We worry about bills and can’t see the shining sun. We get a promotion and only see happy babies. We languish and see sadness in the drooping petals of the wild bergamot. Although I take issue with “time to kill,” “time to hate,” and “time for war,” as King Solomon says, there’s a time for everything under the sun, “a time to weep and a time to laugh,” a time to seek comfort and a time to be disturbed.

Who better to disturb us than Mariana Enríquez, the “uncrowned queen of new Latin American neogothic horror.” Enríquez has been publishing fiction and journalism since 1995, when she put out Bajar es lo peor at the ripe age of twenty-one. Since then, she’s published three novels, three story collections, a novelette, and four books of nonfiction, including a travelogue of visits to iconic cemeteries, whose English translation will be available next month.

Things We Lost in the Fire, Enríquez’s second collection—and first book translated into English (2017)—features twelve stories. To call them unsettling would be an understatement, but to call them full-on horror would be an overstatement. Instead, they’re situated somewhere in between. The literal definition of “phantasmagoria” from Merriam-Webster seems apt: “a constantly shifting complex succession of things seen or imagined.” Monsters? Not quite. Ghosts? Not really. Drugs, hallucinations, abuse, and abject poverty present grim realities for these characters, but often the presence of a sound mind—and privileged inheritance—collides into a dissonant psychological reality rather than a full-blown surrealistic universe.

The book takes its title from Low’s 2001 album of the same name.I don’t want to get too in the weeds, but it’s worth mentioning that the record was produced by Steve Albini, the abrasive, sometimes shocking, and unabashedly punk producer and musician who died last year and worked with the likes of PJ Harvey, Nirvana, and The Pixies, among many, many others, often advocating for a natural sound and live, in-studio recording. I mention this mainly because I think Enríquez and Albini probably would have been friends, given her involvement in the punk scene in Buenos Aires. Albini had a thing for shock, as does Enríquez, although I would argue that Enríquez’s shock rises organically from the ugliness of the narrative situation rather than arbitrary gross-out. The title-sharing feels less like a one-to-one reference point and more like an homage to Low’s incomparable “eerie tension,” as one reviewer put it. Mariana Enríquez’s stories are nothing if not rife with eerie tension.

The opening story in the collection, “The Dirty Kid,” follows a graphic designer who grows increasingly obsessed with a houseless child. She watches from the perch of her family’s old home in a neighborhood “marked by…flight, abandonment,” and “the condition of being unwanted.” The narrator is thrown into an existential quandary when the boy is found decapitated. Rumor is the boy was killed by “witch-narcos.” The news and the police are unreliable. The main character tries to take matters into her own hands, but her obsession shifts into an unexpected violent encounter with the kid’s mother.

The “Intoxicated Years,” a standout in the collection, follows three adolescent girls through five years of intense friendship as they bond over a shared lack — fathers, money, political and parental stability. Systems and institutions fail them, so they seek solace with each other and with drugs. On the bus one evening, they witness a young woman request a stop by a forest, where she wanders off and is never seen nor heard from again. Drunk fathers, gin, and punk boyfriends push them to their limits, and the violence enacted by one of the girls at the end of the story feels both cathartic and inevitable.

“An Invocation of the Big-Eared Runt” follows Pablo, a murder tour guide. As Pablo becomes increasingly estranged from his wife and six-month-old child, the methods, tools, and weapons of Buenos Aires’s most famous killers begin to haunt (and taunt) him. He hallucinates sightings of Argentina’s most famous killer. When his wife asks him to get a new job, he grows defensive, clinging to it and justifying it as a necessary security. “It was all the baby’s fault,” he thinks. You can imagine where this might go—I’ll leave it to the curious to seek out the ending. As a father, this one got under my skin.

Two of the most disturbing stories, “The Neighbor’s Courtyard” and the title story, revolve around the mystery of gruesome violence. “The Neighbor’s Courtyard” follows Paula, a former social worker who is fired for getting drunk and high while overseeing a children’s shelter. Her father dies. She moves. She descends into a depression and berates herself for it all. One night, she hears a pounding at the door, and her husband dismisses her. Later, Paula sees a child—or something like a child—chained up in the neighbor’s courtyard. When her husband tells her it’s nothing, “You’re crazy,” and, “You don’t even realize you’re hallucinating!” she takes it upon herself to ransack the neighbor’s apartment for evidence. It’s a gaslighting story to end all gaslighting stories. How often do men trivialize, ignore, or minimize women’s concerns, fears, anxieties? Much more often than we realize, sadly. I want to give this story to all my straight, male friends.

The title story—a quick warning here if you’re squeamish about domestic violence—follows Silvina*, a young woman who watches on as a burn victim on the subway accounts “about the months of infections, hospitals, and pain.” Her face is described as a “maroon mask crisscrossed by spiderwebs.” She taunts people for showing extra skin in the summer, getting close to them and occasionally kissing them on the cheek. She “preaches” about how her husband poured alcohol over her after discovering her infidelity and lit her on fire. A famous soccer player repeats the act, which leads to reports, gossip, and hedging in the media. “Men were burning their girlfriends, wives, lovers all over the country.” Women begin to burn themselves in protest. Silvina’s mother’s friend, “head of a secret hospital for the burned,” tells her, “Burnings are the work of men. They have always burned us. Now we are burning ourselves. But we’re not going to die; we’re going to flaunt our scars.”

Megan McDowell, who has translated some of my favorite Latin American writers, from Alejandro Zambra to Samanta Schweblin, puts Enríquez’s stories in necessary historical context in the translator’s note:

Argentina's 20th century was scarred by decades of conflict between leftist guerrillas and state and military forces. The last of many coups took place in 1976, three years after Mariana Enríquez was born, and the military dictatorship it installed lasted until 1983. The dictatorship was a period of brutal repression and state terrorism, and thousands of people were murdered or disappeared.

As dictatorship squeezes systems, and as systems squeeze the work force, and as the work force squeezes men and women, often the inheritors of this culture-wide trauma have nowhere to go for help. Young and vulnerable women scrap for dignity. In such a pressure cooker, obsession—intellectualizing suffering and witness to suffering—often leads to inevitable violence.

I’m reminded of Celia Mattison’s wonderful essay “The Scream Gap,” where she explores our appetite for the loud suffering of white women in film and TV. She says this:

“…the scream is a step in how men culturally understand how women endure public oppression and private frustration. If the scream becomes a go-to expression not just of emotion but of “Good Acting,” it flattens acting as an art form and leaves even less space for Black actresses and other actresses of color.”

Mariana Enríquez understands that women suffer in silence, yes—their worries tamped under the weight of men’s impatience—and out loud, with each other, or misdirect their private frustration in ways other than the scream. Enríquez’s women never scream. They abjure screaming, curdling into dark and private depressions that can only, if ever, manifest in the uncanny, the horrific, the violent. Dictators and parents are no help, nor are husbands and boyfriends. So, women turn their attentions to the oppression they can see. They obsess. They try, in their own ways, to help. They worry, they fret, they drink, they quietly endure, they explore, they investigate, they take matters into their own hands. And you can’t help but root for them even as they throw themselves onto the coals.

+++

I’ve said it before and I’ll say it again: I want people to fall in love with reading, period. I don’t care what you read. Just take the time to find enough stillness of body and mind to take in someone else’s daydream, vision, mind, life story. Novels and stories, to me, are like guided meditation. The best ones work on us, demand more of us, prod us into the deep recesses of our thoughts and experiences. If you’ve ever meditated, you know it’s not easy. Thoughts jabber and twist and throttle. But to return to stillness is an act of willful centering. I’m here, I’m alive, I’m breathing, there’s nothing I have to do. It’s not the same as “Everything is OK.” “Everything is OK” is willful delusion. Everything might not be OK. You might’ve lost your job or a loved one or you’re feeling a gnawing sense of malaise or can’t stand the political climate and are twisted into a frenzy. Good. Now be still. Likewise, reading fiction offers this very same gift, only the story is the one saying “I’m here, I’m breathing, offering other experiences and views and biases and patterns of mind and imaginative flights, and there’s nothing to do but listen and remain attentive.” If the other consciousness grates on you, you have the freedom to put the book down. And if you continue on despite a challenge or degree of difficulty, you have the freedom to talk back—either out loud to the book, in writing, or to your loved ones in the room. When our thoughts rise up, when our texts pour in, when our children whap our shoulders with a KOOSH ball, we have a choice. Return to the dream, the other mind, the other consciousness—the other view, the other perspective, the other opinion, the other imagination—or surrender to the forces calling you back to your reality. Sometimes we need to be called back. The kids need food. The boss needs an email. The FedEx delivery person needs a signature. We need to get groceries for the morning. But sometimes the most compassionate thing we can do, the most expansive thing we can do, is shut up and listen. Let the world speak. Let the character speak. Let the other view have its moment. Seek comfort if comfort is what you need. But don’t deprive yourself of a full view either.

*Most definitely a hat-tip to Silvina Ocampo, the great Argentinian fabulist and gothic story-writer.

+++

Please spread the love to your local libraries, independent booksellers if you can, or shop online at Bookshop. Thanks, as always, for reading.