On Wolves & Sounding Writerly

The thing with vacation books is the thing with every book: which to pack, which to prioritize, and which to carry around like comfort blankets, which to pretend I’ve read or am reading.

Preparing for our Hawai’i trip a few weeks ago, I packed The God of the Woods at the last minute because it was one of the “biggest” books last year, and I’m a little behind on big books, and I thought vacation would be a good time to take a vacation from the way I normally do things. The God of the Woods tells the story of Barbara Van Laar’s disappearance from Camp Emerson, a sleep-away camp in the Adirondacks, in 1975. The slow-burn thriller strikes all the perfect plot notes: withholding information, creating what Benjamin Percy calls a “turnstile of mysteries.” Characters try to knock out lower-order goals. Moore delays gratification and employs the ticking clock. (Barbara can only be missing for so long before the search party gives up). I fell for it, although I only ever really cared about Barbara’s mother Alice, who marries into a wealthy family and is tacitly ridiculed for her lack of book smarts.

Liz Moore’s prose reads less like prose and more like stage direction. You have sentences like this all over the place: “A knock at the door. The first counselors, arriving.” And this: “Silence. She waits.” Fragments abound, and a lot of them stripped of the verb—utility to set the scene and set it quickly.

This prose style reminded me of an old teacher’s repeated chiding. He’d write two words in the margins of our stories that felt like a curse: “Sounds writerly.” Too much flourish on the sentences. We get that it’s humid. Cut the whole paragraph and leave the one phrase. “Ethereal”? “Miasma”? Please. What are you, Updike?

But what sounds like stiff, cold prose to one might sound “muscular” to another. Take Raymond Carver. I plucked this random excerpt from his famous story “A Small, Good Thing:”

Howard and Ann stood beside the doctor and watched. Then the doctor turned back the covers and listened to the boy's heart and lungs with his stethoscope. He pressed his fingers here and there on the abdomen. When he was finished, he went to the end of the bed and studied the chart. He noted the time, scribbled something on the chart, and then looked at Howard and Ann.

Sounds, more or less, like stage direction. We get “went” instead of a more lively verb for “walk,” like shuffle, say, or amble. Simple, active sentences, and only one of them has a subordinate clause.

Raymond Carver’s editor Gordon Lish, who cut some of Carver’s early stories by seventy percent, might be described as wolfish. He courted a young Carver, and, impressed with his compression, sought to compress more. Wolves are everywhere in literature, so it kind of makes sense that they lurk behind the scenes as well.

Which brings me to Wolfish: Wolf, Self, and the Stories We Tell About Fear, another book I brought on vacation. Erica Berry writes about wolf conservation efforts, cultural myths about wolves, and about our responses—fair and unfair—to the animal. Her book isn’t so much a biological survey as it is a wide-ranging study into the meaning of the wolf and “what learning to live with them might teach us about learning to live with ourselves.”

We are taught to fear death. That death, like wolves, are to be avoided. A wolf paw print presents a harbinger of catastrophe. A wolf in sheep’s clothing doesn’t bode well for the wolf, either—whatever lurks behind that fluffy coat is threatening at best and downright wicked at worst.

It’s no wonder wolves appear all over Kelly Link’s The Book of Love, my next vacation read, a 600-odd page novel about three teens on the cusp of adulthood who come back from the dead and strike up a bargain to win their way back into the physical realm by playing parlor games with spirit guides. The first time their spirit guide Bogomil—a sinister, Grim Reaper type—is introduced, he is described as a “wolf-thing,” and “reproachful and ravenous.” Link excels at setting up a world that is fully alive without drowning the reader with detail. Lush descriptions and poetic turns of phrase abound. You never feel backed into a corner, as you sometimes do with maximalist writing. You feel taken care of. You notice the prose if you want to notice it, but most of the time you don’t.

Link, in an interview with The Guardian, says she didn’t take to her MFA classmates’ fondness for Raymond Carver, and that she “found realism, to be honest, somewhat lacklustre.” Instead, she fell in love with Grace Paley. I like to think that my winter of picking through Paley’s Collected Stories somehow brought me to Link by way of some wolfish mystery. Paley’s narrators sound like your fast-talking Jewish aunt who lives in New York and has a wit so quick it could take the frosting off your birthday cake.

Though denser than Carver, Paley would definitely pass the “sounds writerly” test, mostly because things happen quickly and the narrators in both her and Carver’s stories sound less like Steinbeck and more like people talking. Take this bit from East of Eden:

He had a rich deep voice, good both in song and speech, and while he had no brogue there was a rise and a lilt and a cadence to his talk that made it sound sweet in the ears of the taciturn farmers from the valley bottom.

Though I surmise a lot of us would sigh and say that’s beautiful writing, many teachers and editors nowadays wouldn’t let you get away with that kind of abundance. “Lilt” and “cadence”? They mean nearly the same thing. Likely, we’d trim it down to something like this, making it faster and more efficient for the modern reader: “He had a rich voice in song and speech, and there was a cadence to his talk that made it sound sweet to the taciturn farmers from the valley.”

Is one right and the other wrong? Hardly. These are stylistic preferences. In my mid-twenties I fell for the warmth and expansiveness of Steinbeck’s prose, but I had to re-train myself in the ways of the current world. “Turn down the volume,” teachers told me.

All this makes me think of Scott McClanahan, who is possibly the best example of “not being writerly” alive today—unless you count “cussingest” as a writerly description. McClanahan sounds like a dude telling a story at a bar. “You see all kinds of weird shit in Rainelle,” begins the narrator of “The Chainsaw Guy.” McClanahan’s charm comes from his informality and his refusal to stuff his stories with symbols and lengthy metaphors. Hardly a flourish, and never more than you need. “The Firestarter” opens like this:

I went through this weird period about ten years ago where every time I went outside, I saw somebody get hit by a car. The first time it ever happened I was just sitting around my apartment and listening to the drunks shouting from the bar next door. It was Labor Day weekend and I was sitting on the couch watching television. I was just about ready to go to bed when all the sudden—BAM. I heard this big thud outside.

Even the repeated “sitting,” though redundant, charms you into a certain kind of believability. Nicole Rudick, writing for The Paris Review, said this in 2014 about McLanahan’s Crapalachia: “[McClanahan's] voice is wholly unaffected, and his account manages to be both comic and unpretentiously sentimental.”

What sounds writerly to one person sounds like pure beauty to another. I come from reticent, repressed Midwesterners who were raised in rural areas and are leery of book smarts, so to them anything with more than two syllables sounds like showing off. Say it straight and don’t brag would be their “not sounding writerly.” But to someone who grew up among, say, Ivy-League-educated lawyers in Connecticut, sounding writerly would have an entirely different association. Craft is culture, and every culture creates their own values implicitly or explicitly and come to expect those values from their artists.

As I made my way through Link’s The Book of Love, I thought about people owning and reclaiming their place on earth. I thought about the immersion of good storytelling. You know the moment: when you forget about the prose style and slip into a waking dream. I think that’s essentially what we’re asking of young writers—and perhaps ourselves—when we say “sound less writerly.” We’re asking them to tell us a good story and tell it so well we forget it’s being told. Cast a spell. And who can cast a spell better than a wolf?

I thought about wolves and wolfishness a lot as we hiked Manoa Falls and took in the huge swells at the Banzai Pipeline, watching the pro surfers glide through the tube. Was I a wolf? Had we unknowingly become predators feasting off the natural beauty, drunk on the bones of ficus and monkey pod trees? Did native Hawaiians want us here?

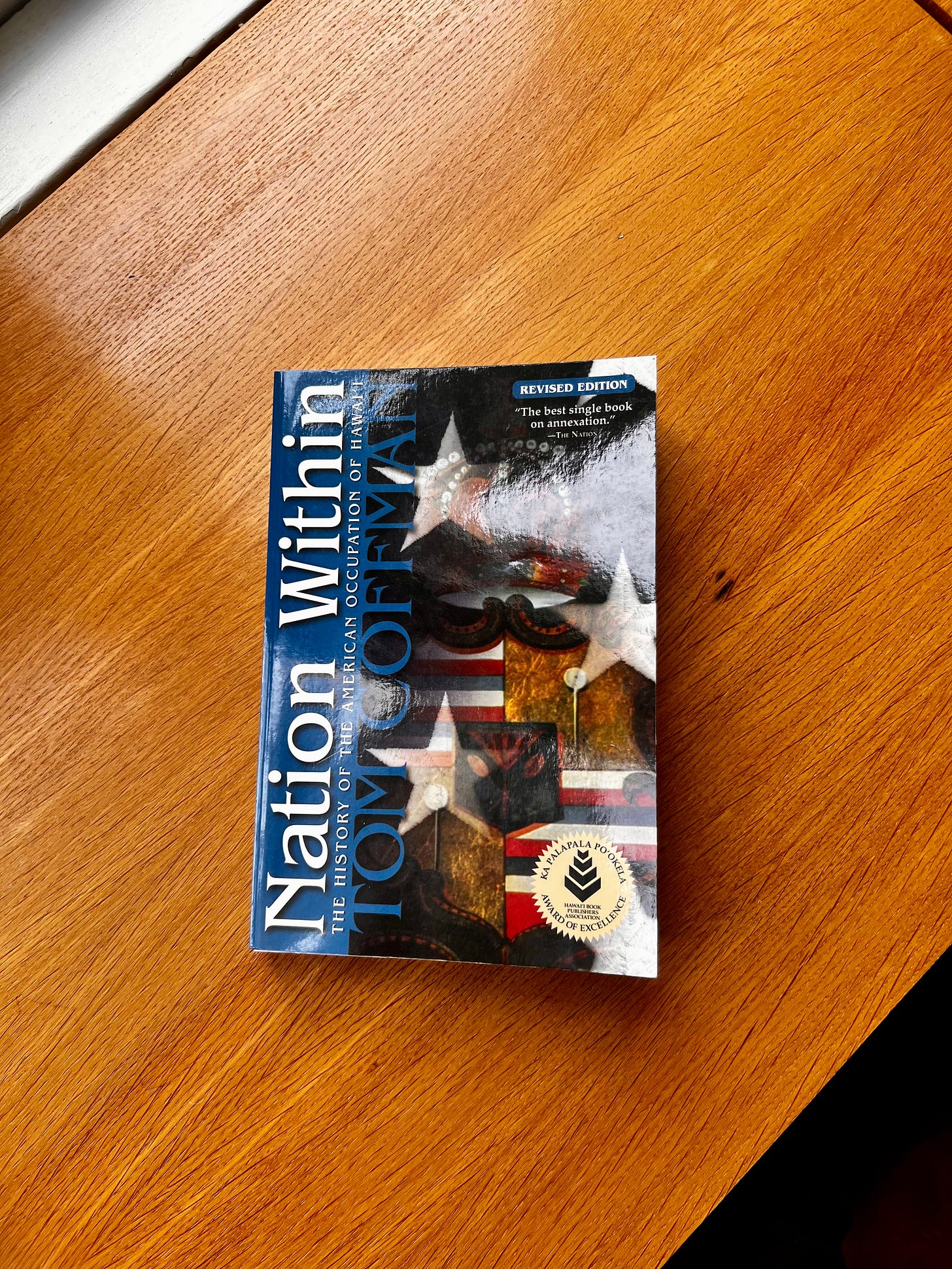

On our last day in O’ahu, we stopped into Native Books in Chinatown, Honolulu, an independent bookstore focusing on the literature of Hawai’i and the Pacific Islands. While browsing, a young man came in an asked the clerk if he could practice his Hawaiian. They slowly walked around the store, speaking in Hawaiian, occasionally pausing to parse out a word. The clerk eventually turned to the young man and said, “Be patient with yourself as you learn. One of the greatest issues we face as Hawaiians is not feeling Hawaiian enough.” I bought Nation Within: The History of the American Occupation of Hawai’i by Tom Coffman and paged through on the plane on the way home. Turns out the wolf has always been at Hawaii’s door. And the mainland, who saw resistance from over 38,000 Native Hawaiians during initial talks of annexation, proved to be a wolf in sheep’s clothing. “Why was Hawai’i taken over?” Coffman asks. “The reasons were essentially military and geopolitical. With ruthless assistance from the missionary descendants, the takeover occurred at the time of America’s choosing and according to its terms.”

How do avoid sounding writerly? You sound like yourself. But how do you sound like yourself when your native tongue has been stripped, bastardized, and commodified? I wonder what tongues lie dormant in the pits of our stomach? What unknown languages have we yet to awaken? How might we understand our own voices when we can’t even hear their historical echo? What wolfish fears have we given into? How do we learn to live with ourselves?

+++

What fun questions do you ask on the plane ride home from vacation? How do you vacation with books? And I’m curious: What sounds writerly to you?

Please spread the love to your local libraries, independent booksellers if you can, or shop online at Bookshop. Thanks, as always, for reading.