Mi Revalueshanary Fren

Timothy Otte on Linton Kwesi Johnson

I first met Tim Otte when we were both floating around the food and beverage scene in the Twin Cities in our twenties. He would frequent coffee shops where I worked, and we would talk books, and later, he helped me curate my tea menu during my stint as a restaurant manager. Since then, we’ve orbited around each other at readings and literary events. He’s a good literary citizen and is immersed in the vibrant Twin Cities poetry scene, and I’ve always trusted his take on books. He told me, one year during the Twin Cities Book Festival, about a little-known author (at the time, to me) named Claudia Rankine. Citizen had yet to come out, and little did a lot of us know about the writer who would so articulately capture our blindness to everyday racism and the illusion of justice. Tim’s poetry and super-smart reviews over at Stanza Break, to me, seem, to quote one of his poems, “feathered and singing,” and he “tells us that we can fix/Our toxic selves.” If you’re in the Twin Cities, I hope to catch you at Next Chapter Books this coming Monday, 10/23, where Tim will be reading poetry as part of a book launch for visiting poet Christy Prahl. J. Bailey Hutchinson and Moheb Soliman are also reading. Details here. Without further ado, here’s Tim.

-Josh

+++

A few years ago, my dad and I were talking about music, which is mostly what we talk about together, and in this particular case we were talking about ska, 2-tone, and reggae, which we both love despite being white guys from the Midwest. Growing up, I remember listening to Toots and the Maytails, The Specials, The Skatalites, Fishbone, The English Beat and, of course, Bob Marley.

Anyhow, in this conversation, my dad put me onto an artist I wasn’t familiar with, a dub-poet and reggae musician named Linton Kwesi Johnson (LKJ, as he’s often known, and how I’ll refer to him here). I don’t know when dad started listening to LKJ, but it would be understandable if he had kept LKJ’s music from me when I was a kid. I’m not a parent, but I can’t imagine trying to keep a seven- or eight-year-old from singing “Inglan Is a Bitch” if they’d heard it, or trying to explain the violence in pieces like “Sonny’s Lettah” or “Five Nights of Bleeding.” So if he had listened to these songs only when I wasn’t around, that would make sense.

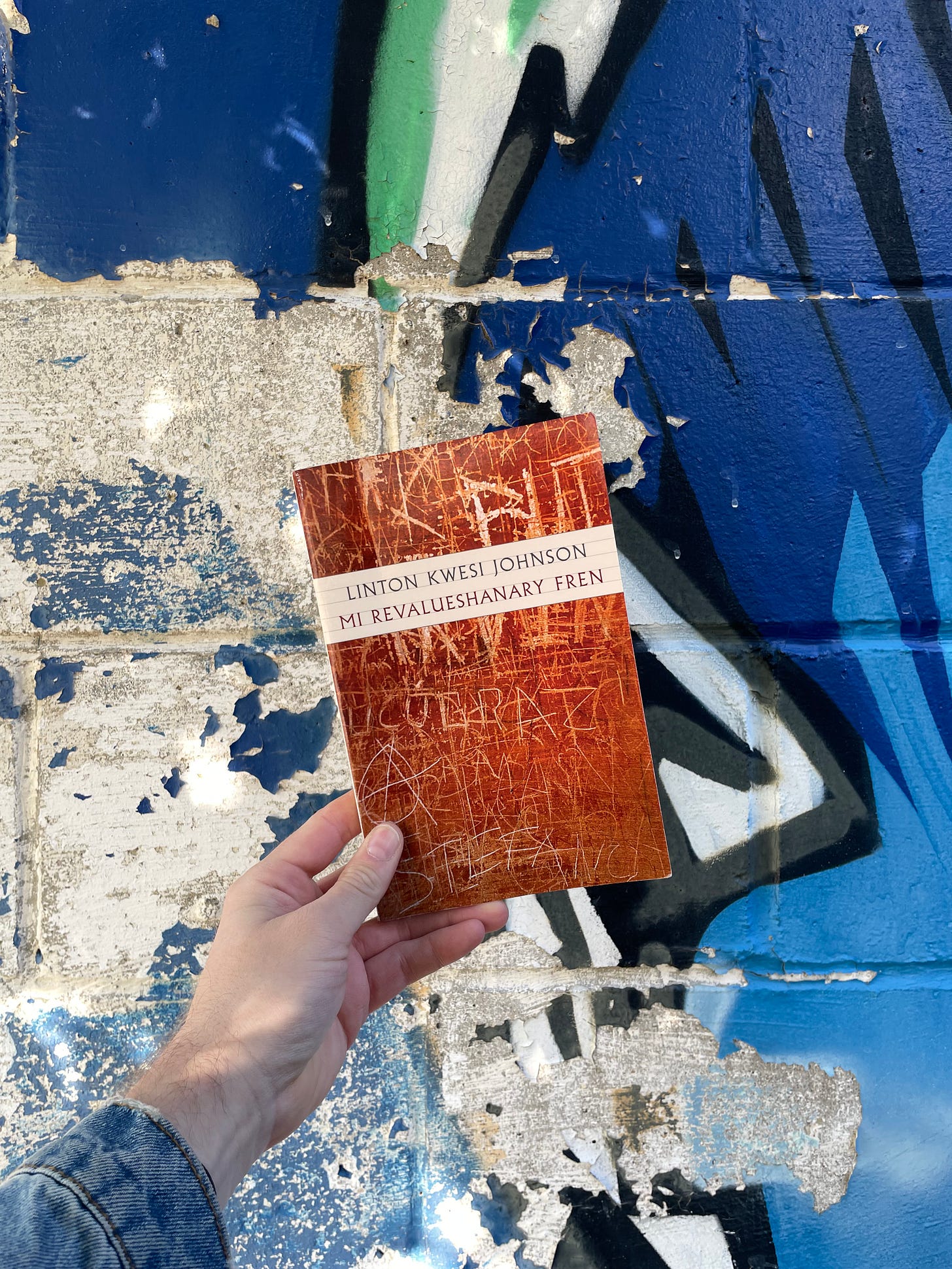

My dad recommended LKJ’s record Forces of Victory and then not long after that I was at a used bookshop and found LKJ’s book Mi Revalueshanary Fren, which I’m here to recommend to you, readers of book(ish). I write my own occasional newsletter called Stanza Break, which is mostly focused on poetry in translation, so when Josh asked me to step in for a day, I thought, “I should recommend some poetry by someone not from the U.S.”

Mi Revalueshanary Fren is a collection of selected poems split into three sections covering the work LKJ was writing in the 70’s, 80’s, and 90’s. It was published in the U.S. in 2006 by Ausable Press, whose backlist is now kept in print by Copper Canyon Press, but the book was originally published in 2002 in the U.K. as part of the Penguin Modern Classics series, making LKJ only the second living poet to be included in the series.

The book includes a CD (remember those?) of a capella performances of the poems, which is key here because LKJ’s poems are meant to be spoken. He writes in Jamaican Creole, and the poems on the page reflect that. It’s best to say these poems out loud. Mi Revalueshanary Fren is a much better title than “My Revolutionary Friend,” which feels painfully stiff to my ears by comparison. One thing I love about poetry is that it can be a really efficient way to communicate a specific lived experience, a particular embodiment of language. You have to step into LKJ’s voice a little bit to read the poems.

Here, check out the opening of the poem “Tings an Times”

duped

doped

demaralized

dizzied

dazed

traumatized

blinded by resplendent lite af love

dazzled by di firmament af freedam

him coudn deteck deceit

all wen it kick him in him teet

The sonic elements are apparent immediately, from rhyme to alliteration. The phonetic spelling adds to the sonic qualities: “lite af love” has a very different sound than “light of love.” In his introduction, Russell Banks writes,

Jamaican Creole is a language created out of hard necessity by African slaves from 17th century British English and West African, mostly Ashanti, language groups, with a lexical admixture from the Caribe and Arawak natives of the island. It is a powerfully expressive, flexible and, not surprisingly, musical vernacular, sustained and elaborated upon for over four hundred years by the descendants of those slaves [...].

I suspect that the use of Jamaican Creole is one reason LKJ isn’t better known in the U.S. where readers—especially white readers—want a certain kind of legibility in the poetry they read, which LKJ’s poems reject.

I’d bet that LKJ’s politics are another reason for his relative obscurity here. He’s been writing about police brutality, colonialism, and racist politicians since the 1970’s, well before many readers were ready to listen. “Maggi Tatcha on di go / wid a racist show / but a she haffi go,” he writes in “It Dread inna Inglan,” a piece included on his 1978 debut album, Dread Beat an’ Blood. “Time Come” was written in response to the death of David Oluwale in 1969, an incident that led to the first successful prosecution of British police in connection to the death of a black person. LKJ’s has never been “ahead of his time,” it’s just that the violence he’s been documenting is finally being acknowledged in the dominant culture.

In his poem “If I Woz a Tap Natch Poet,” LKJ cites Derek Walcott, Lorna Goodison, Kamau Brathwaite, Jayne Cortez, and Amiri Baraka, among other “tap natch” poets as influences. These touchstones place LKJ in a lineage, and if you’ve ever admired any of those poets, you should read LKJ. Lauded younger writers like Douglas Kearney, Jamila Woods, Harmony Holiday, and Danez Smith, all of whom engage with oral and music traditions, offer a path towards understanding LKJ’s work as well. Again, if you’re a reader of these poets, give LKJ a try.

LKJ’s name occasionally pops up on the betting odds for the Nobel. Big awards are mostly garbage, a metric for determining “good” literature only from a very narrow view of the vast possibilities of art. I love and admire many of the winners, but I’m suspicious of the concept of “best” as it applies to art. That said, if the Swedes asked, I’d join the committee just to bully everyone into giving the prize to LKJ. And then I’d quit.

Timothy Otte is the author of the chapbook Rebound, Restart, Renew, Rebuild, Rejoice (Lithic Press, 2019), a mentor with the Minnesota Prison Writing Workshop, and writer of an occasional newsletter called Stanza Break that focuses on poetry in translation and books outside of a publicity cycle. Otte's poems have appeared in Denver Quarterly, FENCE, Yalobusha Review, Sixth Finch, Vagabond City Lit, and others, and their work has received support from a Minnesota State Arts Board Grant and the Loft Literary Center Mentor Series. He lives in North Minneapolis. More at www.timothyotte.com.