Humane, Difficult, Wise, Moving

Hans Weyandt on 10 books he loved

He would probably debate this statement, because he is a good, humble Minnesotan, but Hans Weyandt is something of a legend in the Twin Cities book world—a true bookseller in his omnivorousness, his enthusiasm for under-sung books, and the care he puts into recommending books. When he ran Micawber’s Books in Saint Paul, one of the great bookstores that, for a time, was my home bookstore but has since been put out to pasture, we would chat, quickly and rapturously about what we’d been reading. I remember buying Teju Cole, William Gaddis, and Rachel Kushner under Hans’s supervision. Later, when he managed Milkweed Books, he hand-sold me Clint Smith’s Counting Descent, before Clint Smith was Clint Smith, after I asked for a poetry recommendation. I fell headlong into the collection during my break from teaching a class at The Loft Literary Center upstairs, and I ran up to my class after the break and read a poem aloud, and we talked about it for half-an-hour. Hans and I were both starry-eyed by Charles D’Ambrosio’s essay collection when that came out, and we both have a thing for Joan Silber, and, as you’ll soon find out, Jenny Erpenbeck. I’m getting drunk with excitement as I type, because how often do you feel like someone understands your world? Simply put: I trust Hans more than anyone else when it comes to books and book recommending. If you live in the Twin Cities, be on the lookout for his occasional pop-ups around town, Just Books. His piece today is a fun little tour through his recent readings. Just pretend he’s walking you through the aisles of the best bookstore imaginable, pulling things down and handing them to you as you increasingly go wobbly with a growing stack. Try not to trip. Pay attention. There’s a lot to learn here, many great books to discover. Stacks on stacks on stacks. Without further ado, here’s Hans Weyandt. - Josh

+++

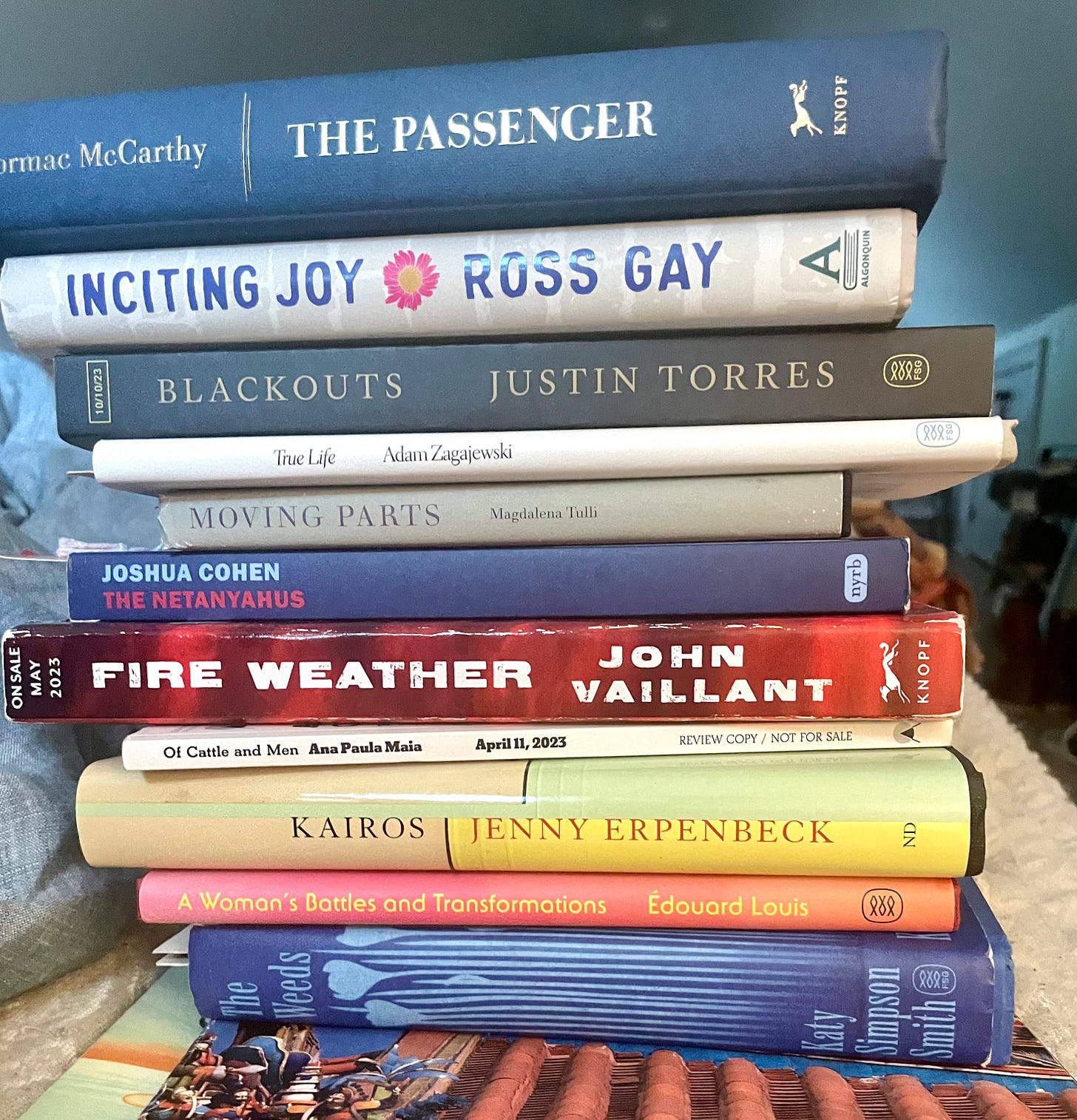

One of the great benefits to joining up with any new venture is that there is little framework or hard rules to adhere to. I think some of Josh’s general guidelines for these book(ish) essays were to pick a book and talk about it and talk about someone the book made us/me/the writer think of. Early yesterday morning I sent him a picture of eleven books and two magazines.

Reading for me is a communal and personal adventure. It can be solitary—even isolationist. But that’s a narrow view and not one of the reasons I go to books for the most part. I like to see what the person next to me is reading on the plane, on the light rail. Reading a sentence or paragraph to one of my kids. “Have you read anything good lately?” being something akin to “How’s it going?” The first question being one most people are more likely to answer honestly and openly. And the simple fact is that none of us read what do we purely based on our own taste or choices. We are influenced by others, and I mean not in the gross sense of bookstagram or any type of electronic or social influencer. Offering a suggestion, receiving one. It is the same base feeling that makes us send someone a song or podcast. Or to say, “Try this…” and pass the person an apricot or piece of good chocolate. It is joy shared. It can be sorrow halved? It is saying this piece of art has made me think or feel or be differently.

I’m not sure exactly why, but in the past few years I’ve gravitated more and more towards fiction. I like being lost in a world or day someone else has wholly invented. It’s like some kind of detox from the internal monologue we all have ticker-taping in our own mind. I’ll read poems or bits of travel essays or cookbooks. I love magazines and zines and periodicals of all kinds, and I ebb and flow through many until they overwhelm like creeper vine. Having said that, I’m not sure why this pull towards novels and some short stories has occurred. I’m sure it has something to do with COVID, with our national and local political situations. With the economy and the rising global temps. With, you know, the world being sort of grim many days. So, for relaxation and enjoyment (you know: fun) I read books. And here is the group I’ve been poking around in lately. I’ve finished some. I’ve started others several times. I wander here and there. It is our great fortune that with books, Jorge Luis Borges was, if anything, a little limiting when he famously said, “The library is unending.”

Kairos is a fascinating title and word. As best I understand it, the word has several meanings that can change depending on its use. The right or opportune moment seems to be the most widely accepted definition from the ancient Greek. Also the name of the god of Opportunity. In current usage, it is more commonly thought of in terms of time or the weather. Jenny Erpenbeck and her translator, Michael Hofmann, have put together a novel that is both a steamy romance fiasco and a thoughtfully written look at time’s passage in both minute and big picture ways. Erpenbeck is a legitimate star in her homeland of Germany and news of a new work is met with much excitement. This is her sixth novel to be published in the United States, and I read this one because Go, Went, Gone is a book I read several years ago and still think of in terms of ideas of migration and boundaries and what ownership of land means—both in the legal sense and a larger, more darkly philosophical sense. She is an author whose work always makes the time spent with it worth it.

My friend Ben and I exchange books a few times a year. What is surprising, given that he manages a Half Price and I’ve spent a couple decades working and hanging around bookstores in St. Paul and Minneapolis, is that neither of us has already read what the other has brought for us. Most recently, he gave me Magdalena Tulli’s novel Moving Parts, which was published in 2005 by Archipelago Books. It’s funny and 133 pages—both summer reading pluses.

An even slimmer volume is Edouard Louis’ A Woman’s Battles and Transformations, which is a thoughtful and bittersweet look at his mother—kicked off by finding a picture of her from when she was twenty years old and understanding that he knew little of the person that he had largely thought of only as mom for his entire life. Ana Paula Maia, compared to both George Orwell and Cormac McCarthy in the jacket copy of Of Cattle and Men from Charco Press is able to escape those lofty comps and carve her own space/niche in a novel I found simple in its narration but in the best sense of that word. This book packs a lot of stuff into 99 pages.

Lest you start to think that I select books that are only novella length, I also tend to read thematically—sometimes by country of location, or author, sometimes by era, sometimes by topic. The comparison to McCarthy, along with his recent death, made me pick up a copy of The Passenger, which is the first of his paired novels that came out simultaneously last year. People can like or dislike mega-famous authors—I long ago stopped wasting time defending authors I like and others don’t. So, if you’ve liked his work, the same foreboding drama unfolds, and the language is his usual brawny and brainy stuff mixed with some high level mathematics and underwater divers. I’m not finished, but it has been fun.

John Vaillant is a Canadian writer whose non-fiction focuses on singular events and then fan outward to show their place in a larger continuum or history. Fire Weather starts with the 2016 Fort McMurray fire in Alberta. An event that was catastrophic for the oil industry and a sign of what has obviously become more normal—the haze covering so many parts of our country this spring and summer the effects of similar, but smaller fires. As a palate cleanser to this climate reality (grim), I’ve also spaced Ross Gay’s Inciting Joy out over the past year. His wit comes with loss, and the joy he speaks of isn’t about getting what he wants or needs but because it has become a practice. It is something he looks for and most often does find. I’d send him flowers monthly if I knew his address.

My book club has been a gift to my reading life for years, and we read only novels. The next book, Joshua Cohen’s The Netanyahus comes from the celebrated NYRB series. Cohen is a writer who seems to challenge himself with novels whose premise often seem difficult to pull off. But he’s not simply bright beyond what most of us can imagine. His sense of language and history add depth and before you realize what’s happening, you’ve fully bought what he is selling.

The final two books form a sort of bizarre trilogy in my head with the Erpenbeck. Katy Simpson Smith’s The Weeds is a book that somehow forms a through line, botanically, from the Roman Colosseum in 1854 to modern day Mississippi. It’s about love and loss and, yes, plants. It’s mesmerizing. Mesmerizing in different ways is Justin Torres’s highly anticipated follow up to We the Animals. But Blackouts is nothing like his debut, except in its total control and power. There is a lost book—I’m an easy mark for that—but that isn’t why I’ve found myself thinking of this piece of art before I fall asleep and while in line at the grocery store. It comes out on 10-10-23, and I must thank the ever helpful and kind Angela from Moon Palace Books for gifting me this in advance. These three novels create new worlds to be sure, but they rely on the one we live in. They are humane and are trying to achieve something quite difficult. They ask you to put down whatever else you could be doing and step into their pages. They are wise and moving. They are meaningful. That’s what I’m hoping for from any work of creative writing.

Hans Weyandt is a reader and still occasional bookseller from St. Paul, MN. He lives in Minneapolis.

+++

Have you read any of these books recently? Please comment below. We’d love to hear your thoughts. Friendly reminder: please support your local libraries and/or your local independent booksellers, or shop online at Bookshop, which allows you to support a bookstore of your choosing. Thanks, as always, for reading.